FAQ

You can find the answers to some more technical and complex questions here.

You might also like to look at our Ask Me Anything videos, which often cover these questions in more detail.

What is Pact good for?

Pact is most valuable for designing and testing integrations where you (or your team/organisation/partner organisation) control the development of both the consumer and the provider, and the requirements of the consumer are going to be used to drive the features of the provider. It is fantastic tool for developing and testing intra-organisation microservices.

What is Pact not good for?

- Testing APIs where the number of consumers is so great that direct relationships cannot be maintained between the consumer teams and the provider team.

- Performance and load testing.

- Functional testing of the provider - that is what the provider’s own tests should do. Pact is about checking the contents and format of requests and responses.

- Situations where you cannot load data into the provider without using the API that you’re actually testing (eg. public APIs). Why?

- Testing “pass through” APIs, where the provider merely passes on the request contents to a downstream service without validating them. Why?

Who would typically implement Pact?

Pact is generally implemented by developers, during development. While some testers do write Pact tests, the code-first, white-box nature of Pact testing means that whoever writes the tests needs to have a strong understanding of the code under test, how to write code, how to use the existing testing libraries (eg. Jest, JUnit) and build tools (eg. Maven, npm), how to create and inject stubs, as well as how to use the Pact library itself. Testers who do not have this experience struggle with Pact, and we suggest pairing with a developer in this situation. Business analysts and testers can still benefit from the presence of contracts by using them to understand the underlying interactions between the applications.

The consumer team is responsible for implementing the Pact tests in the consumer codebase that will generate the contract, and for publishing it to a shared location (usually a Pact Broker). The provider team is responsible for setting up the Pact verification task in the provider codebase, and for writing the code that sets up the correct data for each provider state described in the contract. Both teams are responsible for collaborating and communicating about the API and its usage! Remember that contracts are not a substitute for good communication between teams.

What is the difference between contract testing and functional testing?

See this page under the Consumer best practices section.

Can I generate my pact file from something like Swagger?

Contract testing allows you to take an integration test that gives you slow feedback and replace it with two sets of "unit" tests that give you fast feedback - one set for the consumer, using a mock provider, and one set for the provider, using a "mock consumer". The pact file is the artifact that keeps these two sets of tests in sync. To generate the pact file from anything other than the consumer tests (or to hand code it) would be to defeat the purpose of this type of contract testing. The reason the pact file exists is to ensure the tests in both projects are kept in sync - it is not an end in itself. Manually writing or generating a pact file from something like a Swagger document would be like marking your own exam, and would do nothing to ensure that the code in the consumer and provider are compatible with each other.

Something that could be useful, however, is to generate skeleton Pact test code from a Swagger document. If you're interested in working on this, have a chat to the maintainers on the Pact Slack.

How do I use Pact with UI frameworks like React or Angular?

The best way to use Pact on the consumer side is to focus the tests on just the code that makes the HTTP request, and bypass as much of the framework specific code as possible. You can read more about why that is so here. You can read about how to use Pact to support your UI testing using stub servers here. You can see some examples of using Pact to test consumer code here and a pact-js workshop here.

Why doesn't Pact use JSON Schema?

Whether you define a schema or not, you will still need a concrete example of the response to return from the mock server, and a concrete example of the request to replay against the provider. If you just used a schema, then the code would have to generate an example, and generated schemas are not very helpful when used in tests, nor do they give any readable, meaningful documentation. If you use a schema and an example, then you are duplicating effort. The schema can almost be implied from an example.

Why does Pact use concrete JSON documents rather than using more flexible JSONPaths?

Pact was written by a team that was using microservices that had read/write RESTful interfaces. Flexible JSONPaths are useful when reading JSON documents, but no good for creating concrete examples of JSON documents to POST or PUT back to a service.

Why is there no support for specifying optional attributes?

Firstly, it is assumed that you have control over the provider's data (and consumer's data) when doing the verification tests. If you don't, then maybe Pact is not the best tool for your situation.

Secondly, if Pact supports making an assertion that element $.body.name may be present in a response, then you write consumer code that can handle an optional $.body.name, but in fact, the provider gives $.body.firstname, no test will ever fail to tell you that you've made an incorrect assumption. Remember that a provider may return extra data without failing the contract, but it must provide at minimum the data you expect.

The same goes for specifying "SOME_VALUE or null". If all your provider verification test data returned nulls for this key, you might think that you had validated the "SOME_VALUE", but in fact, you never had. You could get a completely different "SOME_VALUE" for this key in production, which may then cause issues.

The same goes for specifying an array with length 0 or more. If all your provider verification data returned 0 length arrays, all your verification tests would pass without you ever having validated the contents of the array. This is why you can only specify an array with minimum length 1 OR a zero length array.

Remember that unlike a schema, which describes all possible states of a document, Pact is "contract by examples". If you need to assert that multiple variations are possible, then you need to provide an example for each of those variations. Consider if it's really important to you before you do add a Pact test for each and every variation however. Remember that each interaction comes with a "cost" of maintenance and execution time, and you need to consider if it is worth the cost in your particular situation. You may be better off handling the common scenarios in the pact, and then writing your consumer to code to gracefully handle unexpected variations (eg. by ignoring that data and raising an alert).

Why are the pacts generated and not static?

- Maintainability: Pact is "contract by example", and the examples may involve large quantities of JSON. Maintaining the JSON files by hand would be both time consuming and error prone. By dynamically creating the pacts, you have the option to keep your expectations in fixture files, or to generate them from your domain (the recommended approach, as it ensures your domain objects and their JSON representations in the pacts can never get out of sync).

- Provider states: Dynamically setting expectations on the mock server allows the use of provider states, meaning you can make the same request in different tests, with different expected responses. This allows you to properly test all the code paths in your consumer (eg. with different response codes, or different states of the resource). If all the interactions were loaded at start up from a static file, the mock server wouldn't know which response to return. See this gist as an example.

How do I test against the latest development and production versions of consumer APIs?

See this article.

What does PACT stand for?

- Pretty Awesome Contract Testing?

- Provider And Consumer Tests?

- ???

Actually, it doesn't stand for anything. It is the word "pact", as in, another word for a contract. Google defines a "pact" as "a formal agreement between individuals or parties." That sums it up pretty well.

Why Pact may not be the best tool for public testing APIs?

Each interaction in a pact should be verified in isolation, with no context maintained from the previous interactions. Tests that depend on the outcome of previous tests are brittle and land you back in integration test hell, which is the nasty place you’re trying to escape by using pacts.

So how do you test a request that requires data to already exist on the provider? Provider states allow you to set up data on the provider by injecting it straight into the datasource before the interaction is run, so that it can make a response that matches what the consumer expects. They also allow the consumer to make the same request with different expected responses (eg. different response codes, or the same resource with a different subset of data).

If you use Pact to test a public API, the only way to set up the right provider state is to use the very API that you’re actually testing, which will make the tests slower and more brittle compared to the “normal” pact verification tests.

If this is still a better situation for you than integration testing, or using another tool like VCR, then go for it!

Why Pact may not be the best tool for testing pass through APIs?

During pact verification, Pact does not test the side effects of a request being executed on a provider, it just checks that the response body matches the expected response body. If your API is merely passing on a message to a downstream system (eg. a queue) and does not validate the contents of the body before doing so, you could send anything you like in the request body, and the provider would respond the same way. The “contract” that you really want is between the consumer and the downstream system. Checking that the provider responded with a 200 OK does not give you any confidence that your consumer and the downstream system will work correctly in real life.

What you really need is a "non-HTTP" pact between your consumer and the downstream system. Check out this gist for an example of how to use the Pact contract generation and matching code to test non-HTTP communications.

Do I still need end-to-end tests?

TL;DR: It depends

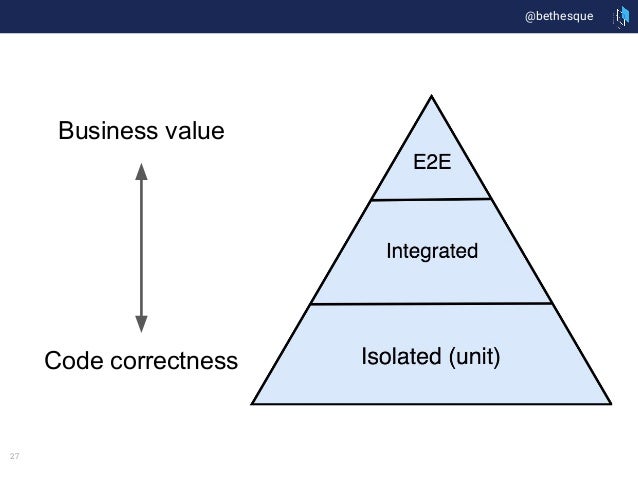

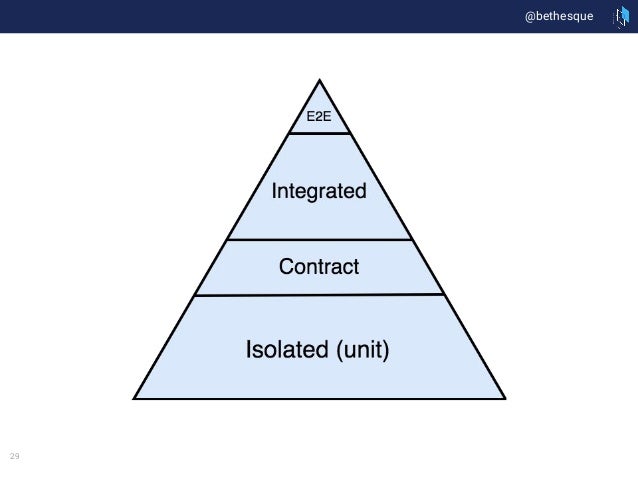

Contract tests replace a certain class of system integration test (the ones you do to make sure that you're using the API correctly and that the API responds the way you expect). They don't replace the tests that ensure that the core business logic of your services is working.

The value of contract tests is that they allow you to shift effort from high maintenance, slow feedback tests to low maintenance, fast feedback tests, reducing the overall effort required to release.

We often see end-to-end integration tests used as a catch all across integration, functional and acceptance testing (in the pyramid below, this would be represented as a bigger portion of the "E2E" part of the triangle). Specifically, we see them used as a proxy for provider functional tests. Separating the integration from the functional aspects often relieves end-to-end tests of a lot of their duties, and in some cases they can be replaced altogether. Read on to see how.

Watch a video: replacing end-to-end integration tests

The following video goes into a little more depth about how to replace your end-to-end tests using a combination contract testing and other strategies:

Or, watch the full series on contract testing.

Before contract tests

After contract tests

The real question is: how many end-to-end tests do you really need once you have contract tests, and in which environment - test or production? The answer to this question depends on your organisation's risk profile.

There is generally a trade off between the amount of confidence you have that your system is bug free, and the speed with which you can respond to any bugs you find. A 10 hour test suite may make you feel secure that all the functionality of your system is working, but it will decrease your ability to put out a new release quickly when a bug is inevitably found. This is related to the concept of MTTR and change lead time (see "The Four Key Metrics" below).

If you work in an environment where you prioritise "agility" over "stability", then maybe you would be better off investing the time that you would have spent maintaining end-to-end tests in improving your ability to find and fix bugs more quickly. For example:

- increasing the proportion of functional tests in your provider code base

- using semantic monitoring techniques like synthetic transactions to let you know if any important functions are not working in production

- adding correlation IDs to your code

- setting up aggregated logging

- improving your alerting

- optimising your builds so that they run faster

If you work in a more traditional "Big Bang Release" environment, choose end to end tests that focus on the core business value provided by your system, rather than on tests that try to check that the HTTP requests are being done correctly.

The Four Key Metrics

Lastly, we find that the four key metrics from DORA that correlate to high performing organisations are great ways to measure and report on your contract testing initiative. These metrics are:

- Deployment frequency: how often do you release?

- Lead time for change: how long does it take to get a release from from commit to production?

- Change failure rates: how often does a change result in a failure as a percentage of all changes?

- MTTR: how long does it take to recover from a failure (e.g. fix/rollback)

Summary

- Measure your current performance against the four key metrics

- Review your current test strategy and portfolio - are you using end-to-end integration tests as a catch all and can you start to re-invest effort in other areas of testing?

- Set targets for the four key metrics based on what is a reasonable starting point for your team and communicate this goal

- Move tests designed to check the provider is behaving as expected into the provider's code base

- Replace the integration testing aspects of your end-to-end tests with contract tests

Can I use Pact for UI tests?

See Using Pact to support UI testing.

How can I handle versioning?

Consumer driven contracts to some extent allows you to do away with versioning. As long as all your contract tests pass, you should be able to deploy changes without versioning the API. If you need to make a breaking change to a provider, you can do it using the expand and contract pattern.

Using a Pact Broker, you can tag the production version of a pact when you make a release of a consumer. Then, any changes that you make to the provider can be checked against the production version of the pact, as well as the latest version, to ensure backward compatibility.

If you need to support multiple versions of the provider API concurrently, then you will probably be specifying which version your consumer uses by setting a header, or using a different URL component. As these are actually different requests, the interactions can be verified in the same pact without any problems.

How can I make a breaking change to a provider?

If you need to make a breaking change to a provider, you can do it in a multiple step process using the expand and contract pattern.

- Add the new fields/endpoints to the provider and deploy.

- Update the consumers to use the new fields/endpoints, then deploy.

- Remove the old fields/endpoints from the provider and deploy.

At each step of the process, all the contract tests remain green. This pattern is supported well by consumer driven contracts because it is easy for a provider to determine if/when all the consumers have dropped use of the old field by removing it in a local development environment and running the pact verification tests.

Is there a Jenkins plugin for Pact?

There is no Jenkins plugin for running Pact tests because a plugin is not needed. Pact tests run as part of the "isolated" test phase of an application's automated test suite, during (for the consumer side) or immediately after (for the provider side) the application's unit test suite. They should be able to be run on local developer machines before pushing to a CI system. Any dependency on a CI plugin would require a difference between how the tests are run locally, and how they run on CI, which would make it harder to reproduce and fix failures.

What is the difference between the Pact Broker and the mock service?

The Pact mock service (and stub service) simulates a provider, and runs on your local development or CI machine for the duration of the Pact tests. The Pact Broker is a permanently running, externally hosted service with an API and UI that allows you exchange the pacts and verification results that are generated by the Pact tools.

What is the difference between Pact, the Pact Broker and PactFlow?

Pact is an open source tool implemented in multiple languages that allows you to perform contract tests on an integration point using a simulated provider and a simulated consumer. It runs on your local development development or CI machine for the duration of the Pact tests.

The Pact Broker is a permanently running, externally hosted application with an API and UI that allows you exchange the pacts and verification results that are generated by the Pact tools. Like Pact, it is open source software. You can read more about the Pact Broker here.

PactFlow is a commercial fork of the Pact Broker, and adds features required to use Pact at scale. These include SSO, user management, an improved UI, and secrets. You can read more about PactFlow here.

Using Pact where the Consumer team is different from the Provider team

Pact is "consumer driven contracts", not "dictator driven contracts". Just because it's called "consumer driven" doesn't mean that the team writing the consumer gets to write a pact and throw it at the provider team without talking about it. The pact should be the starting point of a collaborative effort.

The way Pact works, it's the pact verification task (in the provider codebase) that fails when a consumer expects things that are different from what a provider responds with, even if the consumer itself is "wrong". This is a little unfortunate, but it's the nature of the beast. (See this page on pending pacts for how we've fixed this problem.)

Running the pact verification task that gets triggered by the "contract content changed" webhook in a separate CI build from the rest of the tests for the provider is a good idea - if you have it in the same build, someone is going to get cranky about another team being able to break their build.

It's very important for the consumer team to know when pact verification fails, because it means they cannot deploy the consumer. If the consumer team is using a different CI instance from the provider team, consider how you might communicate to the consumer team when pact verification has failed. You should do one of the following:

- Configure a Pact Broker webhook to send a Slack message when a failed verification result is published.

- Configure the pact verification build to send an email to the consumer team when the build fails.

- Have a copy of the provider build run on the consumer CI that just runs the unit tests and pact verification. That way the consumer team has the same red build that the provider team has, and it gives them a vested interest in keeping it green.

Verify a pact by using a URL that you know the latest pact will be made available at. Do not rely on manual intervention (eg. someone copying a file across to the provider project) because this process will inevitably break down, and your verification task will give you a false positive. Do not try to "protect" your build from being broken by instigating a manual pact update process. The pact verify task is the canary of your integration - manual updates would be like giving your canary a gas mask.

How to prevent a consumer from deploying with an invalid contract

Use can-i-deploy:

Use the can-i-deploy feature of the Pact Broker CLI. It will give you a definitive answer if the version of your consumer that is being deployed, is compatible with all of its providers.

For this to work you need to...

Ensure the provider verification results are published back to the broker

As of version 2.0+ of the Pact Broker, and 1.11.1+ of the Pact Ruby implementation, provider verification results can be published back to the broker, and will be displayed on the index page. The consumer team should consult the verification status on the index page before deploying.

One catch - it is only safe to deploy the consumer if it was verified against the production version of the provider.

Some other approaches to consider are:

Use Pact Broker Webhooks:

Trigger a build or Slack notification using webhooks on the Provider as soon as a changed contract is submitted to the server.

Collaboration

Well, for starters, you must be collaborating closely with the Provider team!

Effective use of code branches

It is of course very important that new assumptions on the contract be validated by the Provider before the Consumer can be safely released. Have branches tested against the Provider before you merge into master.

How do I test OAuth or other security headers?

For interactions such as OAuth2 defined by a standard and implemented with a library implementing that standard, we would recommend against using Pact for these scenarios. Standards are well defined and don't change often, and likely you have simpler testing options available (probably something your framework provides).

For APIs that use these headers, things are a little more complicated, particularly on the provider side - the side that actually needs the token to be valid. Why?

When Pact reads the pact files for verification on the Provider side, it needs to have a valid token, and if that token has been persisted in a Pact file it has probably expired.

Here are some options

- Create a Mock authentication service used during testing - this gives you the best control.

- If using the JVM, you can use request filters to modify the request headers before they are sent to the Provider.

- If using Pact JS you can use request filters

- If using Pact Go you can use request filters

- Configure a relaxed OAuth2 validation service on the Provider that accepts any valid headers, so long as the match the spec (e.g.

Authorizationheader). You might leverage the provider states feature for this. - Use Ruby's

Timecopor similar library to manipulate the runtime clock. - Use the

--custom-provider-headeroption if you are using one of the implementations that wraps the Ruby standalone and there are no other options (Python, .NET).- In Python, this is available via the the

headeroption

- In Python, this is available via the the

NOTE: Any option that modifies the request before sending to the running provider increases your chances of missing a key part of the interaction and therefore puts you at risk. Use carefully.

See the following links for some further discussion:

- https://github.com/pact-foundation/pact-ruby/issues/49#issuecomment-65346357

- https://groups.google.com/forum/#!searchin/pact-support/oauth|sort:relevance/pact-support/zTnDlOgdYhU/tq_Yx8MnIgAJ

- https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/pact-support/tSyKZMxsECk

- http://stackoverflow.com/questions/40777493/how-do-i-verify-pacts-against-an-api-that-requires-an-auth-token/40794800?noredirect=1#comment69346814_40794800

How do I deal with a situation where there are multiple systems involved in a scenario?

There are multiple situations where you need to traverse more than 2 systems in a single scenario. For example, consumer A calls provider B, which calls downstream dependency provider C, which then calls another downstream dependencies provider D and and so on.

Another common example is where one system calls out to another system first to fetch an authentication token such as a JWT. In this case, there is an API call from consumer A to auth provider B, which is then able to call auth server C.

Where possible, you should try to isolate interactions between two services at any one time. We would generally recommend stubbing out these systems.

See https://gist.github.com/bethesque/43eef1bf47afea4445c8b8bdebf28df0 for some more detail on how you might achieve this, and read our advice on dealing with auth services.

How do I test auth cookies?

You have a Provider that sends a Set-Cookie header, which is a core part of the contract, and your consumer (usually a website) needs to send back a Cookie: ... header to authenticate.

The core of the challenge here, is that you're not really writing any code on the consumer side that implements this contract - the browser does it for you.

In this instance you have a few options:

- Not include them in the tests. After all, the consumer code doesn't know about them and you can mock the validation on the provider side if needed

- Include them in the Pact tests, and validate the structure + contents of them on the provider side.

(1) doesn't fully represent the true contract, but (2) would require more code/effort.

In this case, we suggest you need to weigh up the pros/cons. From a purely theoretical perspective, the answer is “you should include it”. But taking a more balanced view, we say test what gives you value. If the cookie is always going to be implicitly added by the browser (because that’s how browser’s behave) and it’s a scenario unlikely to give your team more (useful) information about how the system behaves, whilst costing you effort in maintaining it. Then maybe it’s not worth it.

Sorry, life isn't black and white!

Should the database or any other part of the provider be stubbed?

The pact authors' experience with using pacts to test microservices has been that using the set_up hooks to populate the database, and running the verifications with all the real provider code has worked very well, and gives us full confidence that the end to end scenario will work in the deployed code.

However, if you have a large and complex provider, you might decide to stub some of your application code. You will definitely need to stub calls to downstream systems or to set up error scenarios. Make sure, if you stub, that you don't stub the code that actually parses the request and pulls the expected data out, because otherwise the consumer could be sending absolute rubbish, and the verification task won't fail because that code won't get executed. If the validation happens when you insert a record into the datasource, either don't stub anything, or rethink your validation code.

How do I test binary files in responses, such as a download?

We suggest matching on the core aspects of the interaction - the request itself, and the response headers e.g.

{

state: 'I have a picture that can be downloaded',

uponReceiving: 'a request to download some-file',

withRequest: {

method: 'GET',

path: '/download/somefile'

},

willRespondWith: {

status: 200,

headers:

{

'Content-disposition': 'attachment; filename=some-file.jpg'

}

}

}

Can I test GraphQL?

Yes.

See below, or the Pact JS example.

I use GraphQL, SOAP, Protobufs ... do I need contract tests?

This is a hard one. All we can do is provide some general advice, which can be easily summarised as this:

if there is a possibility that the provider and consumer can get out of sync, then contract tests can help

GraphQL is simply an abstraction over HTTP, and it is entirely possible that the consumer and provider get out of sync. Writing contract tests with Pact turns out to be a relatively trivial exercise, once you understand how the interactions work under the hood.

SOAP is the same. Yes, there is a strongly defined schema, however if the provider changes that schema and deploys before a consumer has updated, boom - client down.

Protobufs is something we are still thinking about, and we've yet to test it with Pact in the wild. It does appear unnecessary as it has mechanisms to deal with backwards compatibility - but if you're willing to investigate, please chat to us and tell us how you go :)

How can I tell if I have good contract test coverage of my provider API?

Contract tests aren't intended to provide any particular percentage coverage of the provider code - that's what the provider's own functional tests are for. The important question to be asking is "what proportion of the consumer code that makes the calls to the provider is covered?". If you execute your consumer Pact tests in a separate step in your test suite, you can use standard code coverage tools to determine whether or not your Pact tests have covered a sufficient percentage of your consumer client code.

While the coverage metric can be helpful, it unfortunately won't be able to tell you whether or not you've covered every semantic variation of an endpoint. Determining that is currently beyond the scope of Pact, but is something that we would love to be able to solve in the future.

Why does computer say no in the can-i-deploy tool?

This is a Little Britain reference (language warning!).

Can I verify my pacts against a deployed instance of a provider?

This is not recommended. Pact is designed to give you confidence that your integration is working correctly before you deploy either application. To achieve this, the verification step must be run against a locally running instance of your provider on a development machine or in CI/CD.

Verifying pacts against an already deployed provider will mean you don't get the benefits that contract testing was intended to provide - fast feedback, easy debugging, reliable tests. It will create a bottleneck as you won't be able to run tests in parallel, and you won't be able to use features like the webhook that trigger builds for different versions of your provider. It is also much more difficult to insert, remove or mock the data required for provider states, to stub external dependencies, and to control areas like authentication.